solidarity infrastructures blog

30.03.24: This blog was originally posted on the course website for Infrastructure Solidarities, a course at School for Poetic Computation that I took from January through March 2024.

navigating through map-making (an infrastructure of solidarity)

Whenever I think about maps, I think about this quote “the map is not the territory”. That is to say, the act of mapping (and impossibility of rendering a 3D space on a 2D object) will always be incomplete, and will always but a partial, incomplete, biased rendering of the space it is rendering. Representations of objects will always be partial. Our mental models are always incomplete.

You can see this in the field of map-making itself: cartography. While cartography is steeped in particular histories of conquest of land and sea, people have always tried to make sense of the spaces in which they live. The act of making maps is not the same as cartography. We often aim to understand, but we do not always aim for control.

At the School of Poetic Computation this year, I applied to the Solidarity Infrastructures course with the aim of making maps, for myself, for others, for experimentation, in solidarity, for rest, for direction. After a few years of interdisciplinary work on the infrastructures of various technology systems (and the burnout and confusion that can come from this kind of oscillation), I was hoping that this course could help me to navigate to somewhere new – a path back towards myself? To somewhere else? To somewhere better? To a place I had not previously imagined?

And so it was! I am so grateful for these 10 weeks. Navigating through the materials (and annotating with others) felt like an exercise in orientation all the time, as we sailed through the oceans of resources, projects, experiments, and conversations that came from our course materials.

Final project

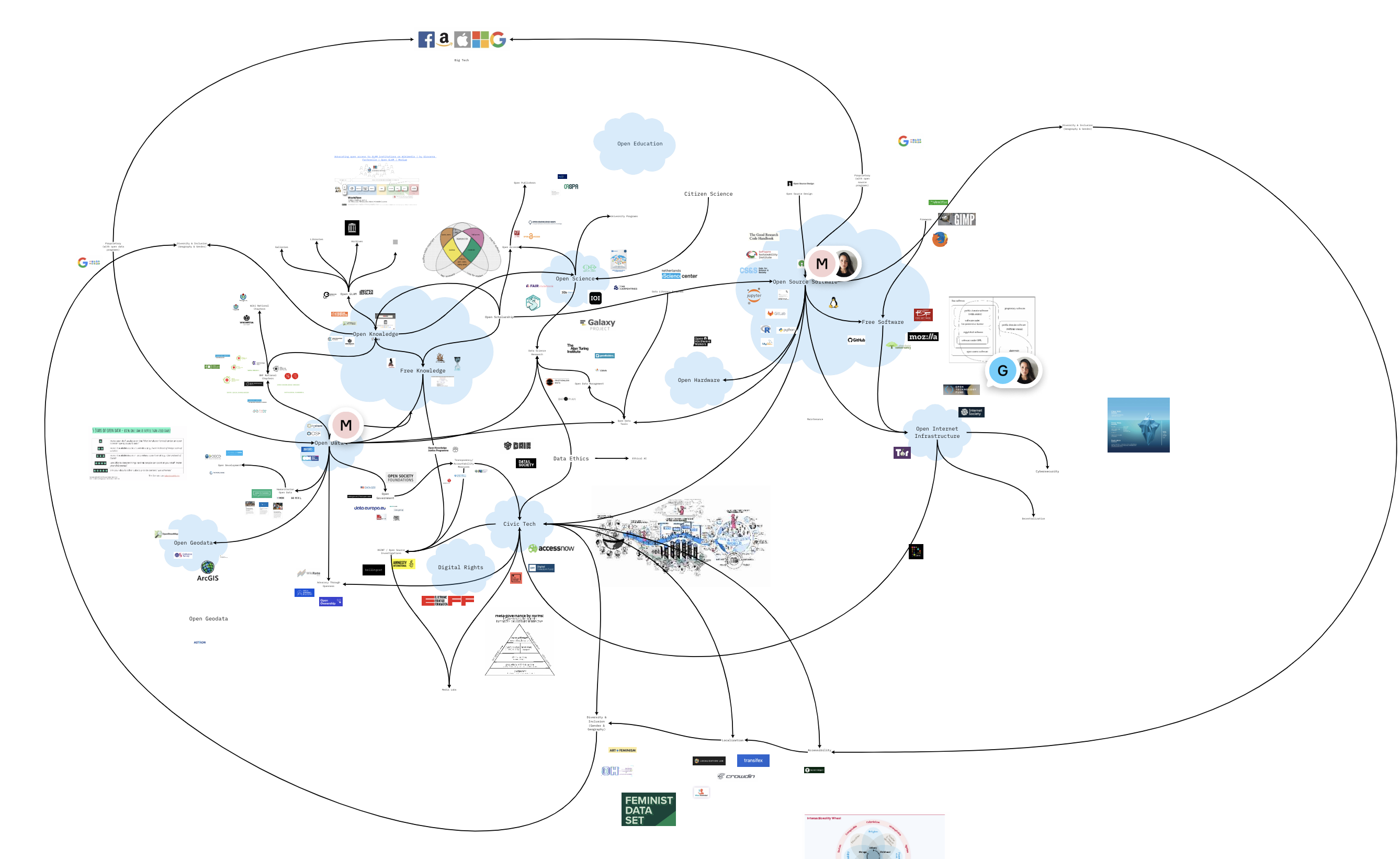

My final project, which you can explore here was more of a messy mind-map: a navigation through the loose and increasingly interconnected themes we explored throughout the class.

But why maps in the first place? How did we get here?

When I look back, it’s funny to realise that I’ve been spending the past 10 years making maps of different types.

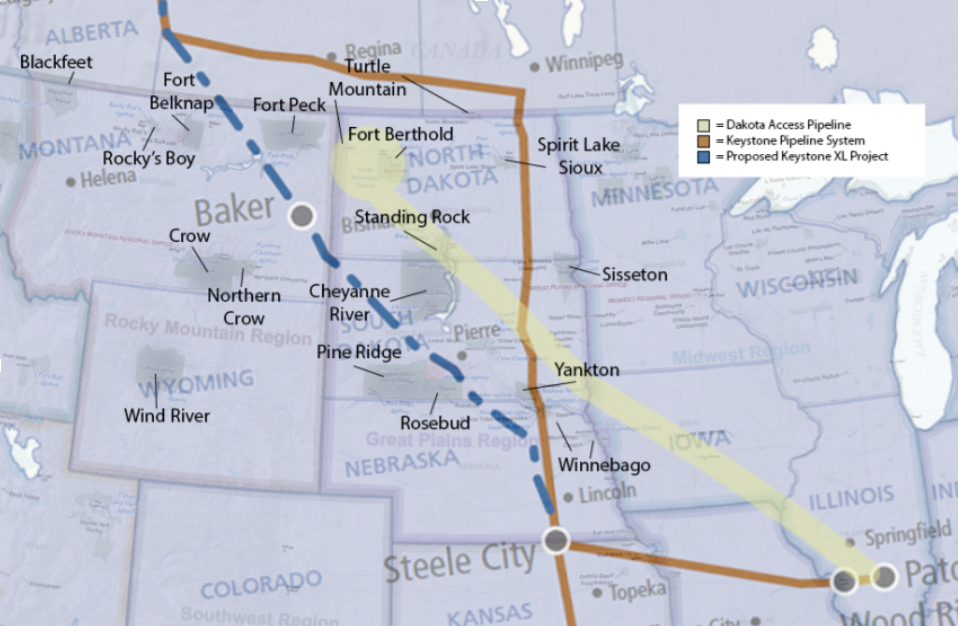

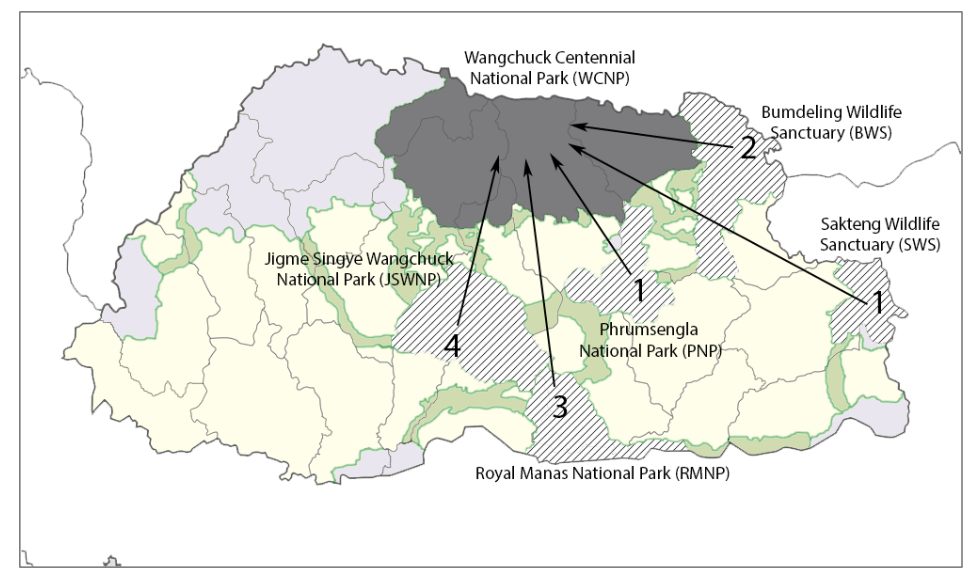

I first entered the world of map-making in 2016, when I started mapping projects for undergraduate classes related to resource extraction and political ecology. The maps were made to demonstrate points that were hard to illustrate otherwise, an aesthetic choice.

Map of pipelines in the northern United States

Map of the Kingdom of Bhutan

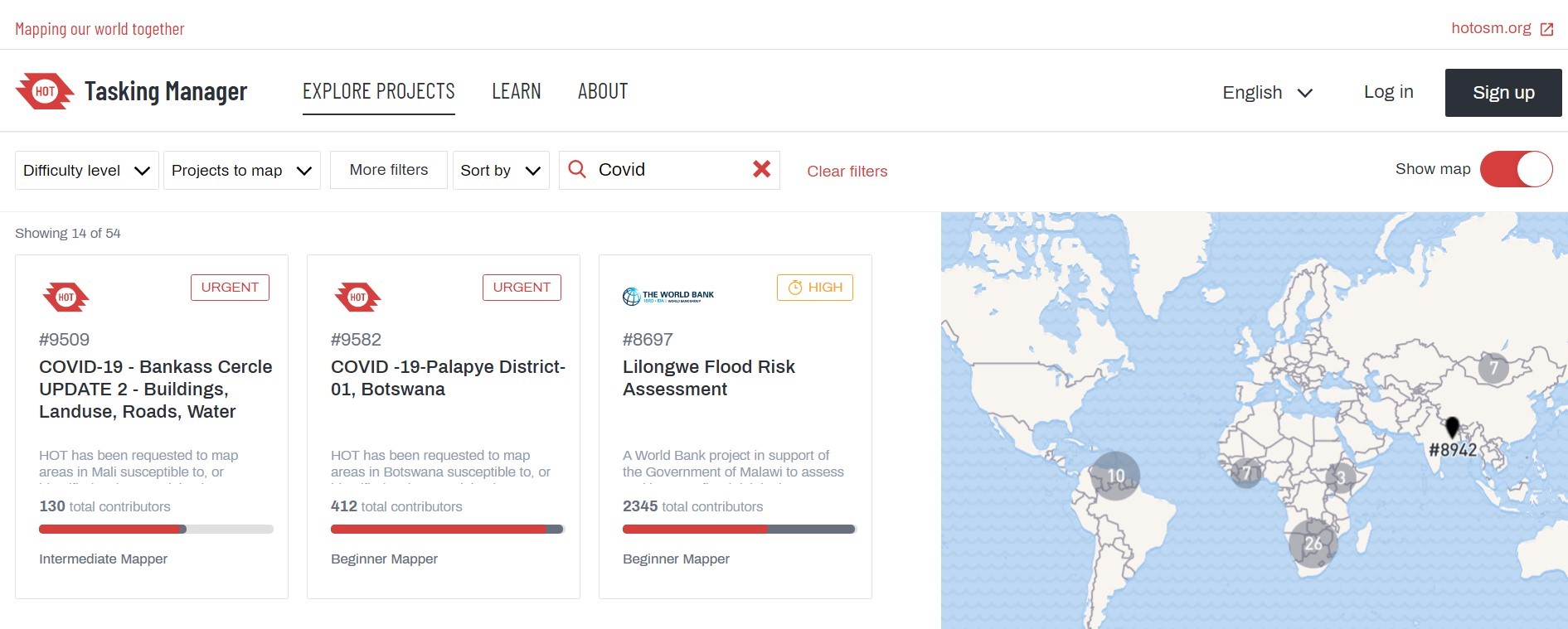

Three years later, in 2020, I somehow found myself making maps all over again during COVID-19, after joining a “mapathon” organised in response to the pandemic.

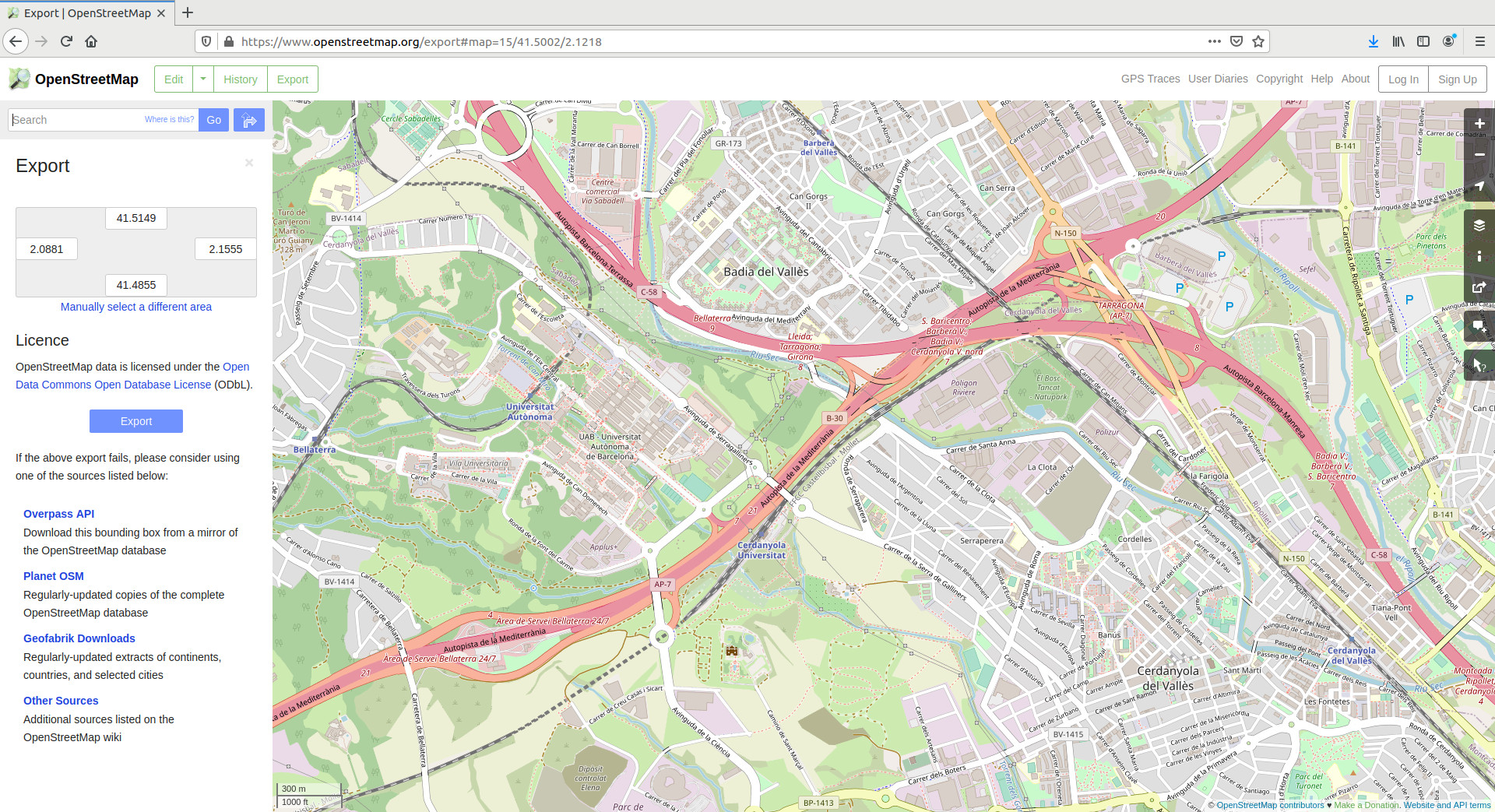

At the time, I was in graduate school, and over the next few years, map-making as a practice slowly consumed me. For almost two years, I pursued an ethnographic study of the “Wikipedia of maps”, a project and database known as OpenStreetMap, and turned my gaze towards the map-makers.

This research introduced me to the world of “crisis maps” and how they configure disaster responses worldwide. Studying who was mapped and why revealed deeply political and contentious questions, and introduced me to the wider world of open practices. It also showed me how the Mercator projection fucked us all up.

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team Tasking Manager

OpenStreetMap interface

As I increasingly learned about the processes behind making maps themselves in the 21st century, I started looking upwards, moving towards the satellite imagery that bely this kind of work, and the technologies that enabled such mapmaking in the first place. I ended up writing about this in Logic Magazine in 2022.

Grasberg Mine, Papua, Indonesia (gold).

In the years since, my understanding of mapping has become less about the explicit assertion of surveillance or control (which it can absolutely be – as Seeing Like a State would assert), and more about trying to understand why we try to make sense of things spatially.

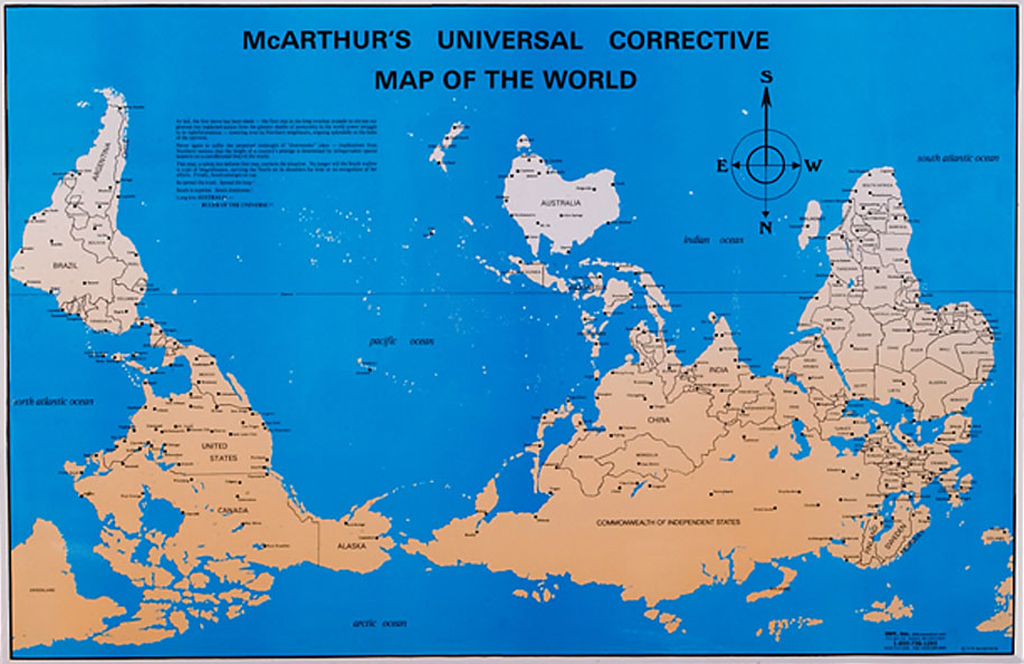

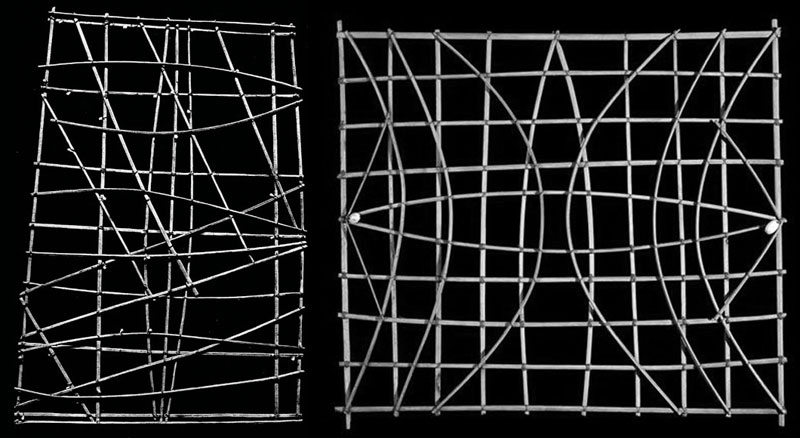

After all, people have always experimented with what it means to represent the world around them. I was interested in other representations – and how they pushed the boundaries of the form of the map, and what new renderings they might inspire.

At the same time, many people are also aiming to rectify the harms of cartography and cartographic practices, which is really important (and very much still ongoing).

McArthur’s Universal Corrective Map of the World (1979)

Navigational systems of the Marshall Islands: stick charts (source)

Over the past few years, maps have started being my way of navigating ecosystems I worked in, from the open ecosystem that I find myself working in now.

Open source ecosystem using miro

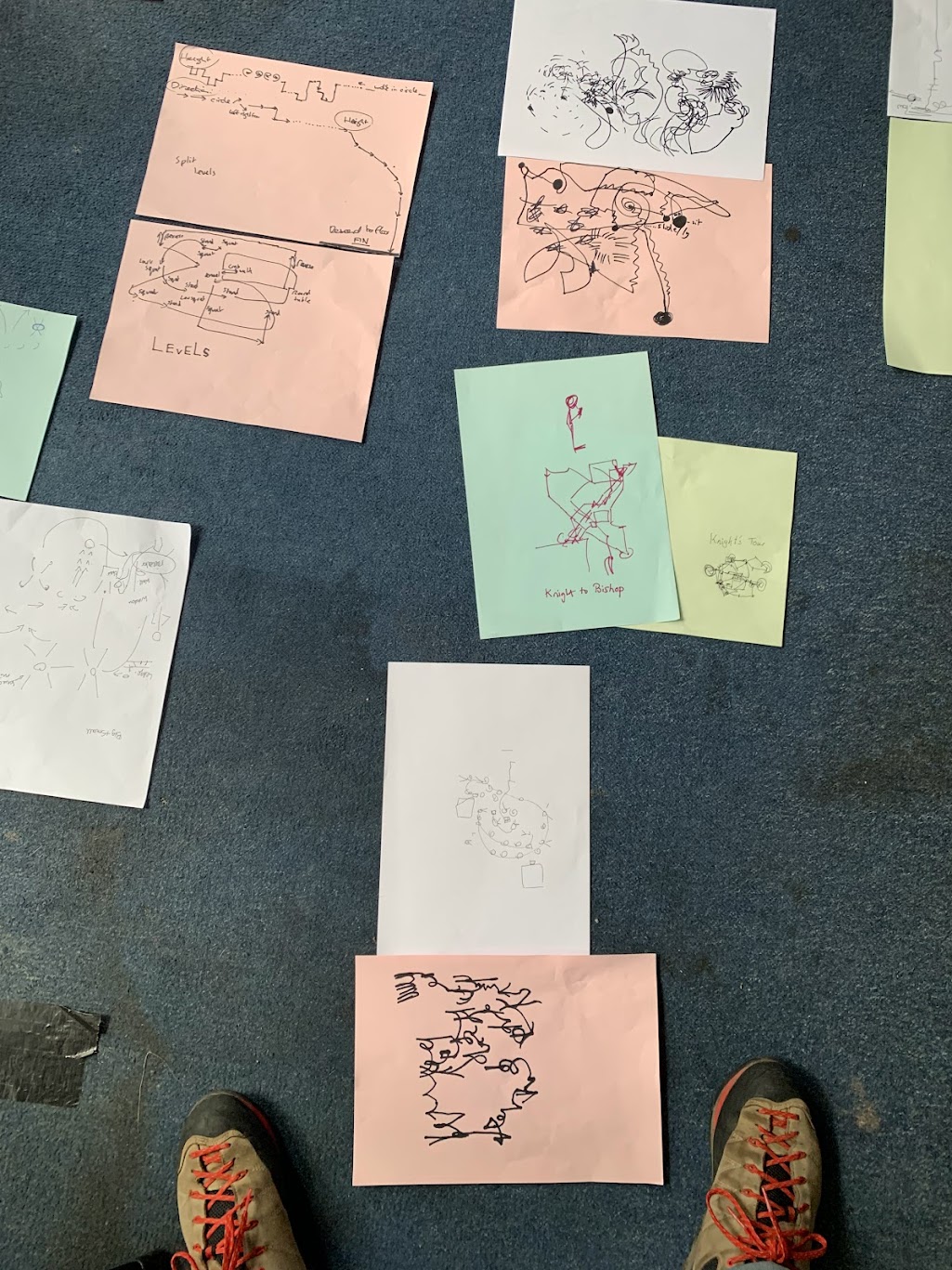

I’ve even started going really small. My maps have become maps of the movements of bodies themselves, in the form of choreography.

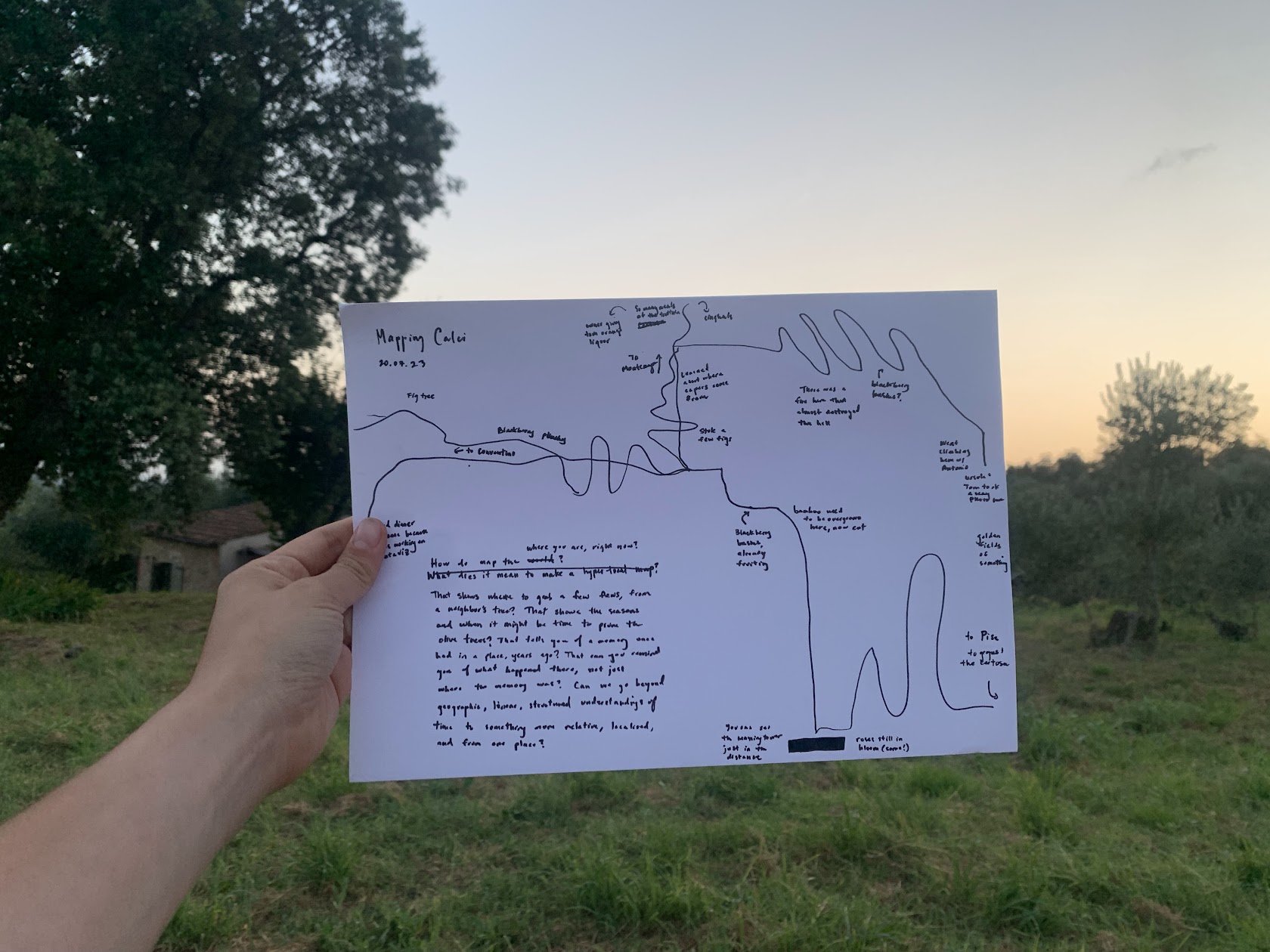

They’ve become maps of memory-scapes, and of of navigating tactile and auditory memories of spaces and places.

Mimicking choreographies, making algorithms with Joana Chicao

Mapping Calci, Italy

I wonder what maps there are to be made, in solidarity, in concert with others. Even this blog felt like a mapping, a retelling, a navigation to some kind of work in progress.

Alice, Meghna and Oren: Thank you for creating and stewarding this space with all of us. I’m excited to nurture the seeds that were planted here.